This fall, the Green Seattle Partnership hosted a workshop with Celeste Mari Williams and Lisa Fink to explore how the words we use impact our success with community-based restoration. Lisa is a PhD candidate in Environmental Sciences, Studies, and Policy with English as a focal department at the University of Oregon, where she is currently an Oregon Humanities Center Dissertation Fellow. She conducts interdisciplinary research at the intersection of Native American and Indigenous Studies, Asian American Studies, critical ecology, and feminist science studies. Celeste is a playwright, former TV animation professional, and current graduate student pursuing an MA in biology with a focus on conservation and community engagement. Her creative and academic work center on interdisciplinary projects that intertwine the arts, science, and social justice to foster trust, empathy, and emotional connection with human and wildlife communities. Their work exists as part of a broader movement to consider language in environmental education and conservation work.

This conversation has come to the forefront of GSP work over the last year. Our March 2021 GSP Newsletter included a short article, Rethinking Our Restoration Rhetoric. Our words have meaning, and we need to update how we talk about plants and non-human relations. We have long demonized these fellow Earth-inhabitants. We want to acknowledge how this use of language has caused harm to members of our community. We are here to not only continue the conversation, but also work towards better relationships with all the living beings in our cities.

Racist Rhetoric in the United States

In recent years we have seen an uptick in racist attacks, in particular when the Trump Administration used racist phrases to describe the COVID-19 virus and pandemic. Prejudice against people from other countries has been core to the story of the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Japanese Internment Camps during World War II are examples of pervasive xenophobia that still exists across the country and in the Seattle-area. As Celeste Mari Williams said in the GSP Just Language Webinar, “Demonizing rhetoric portrayed unwelcome humans as foreign, alien, impure, invaders, and carriers of pestilence and disease. Such language justified atrocities to human life.”

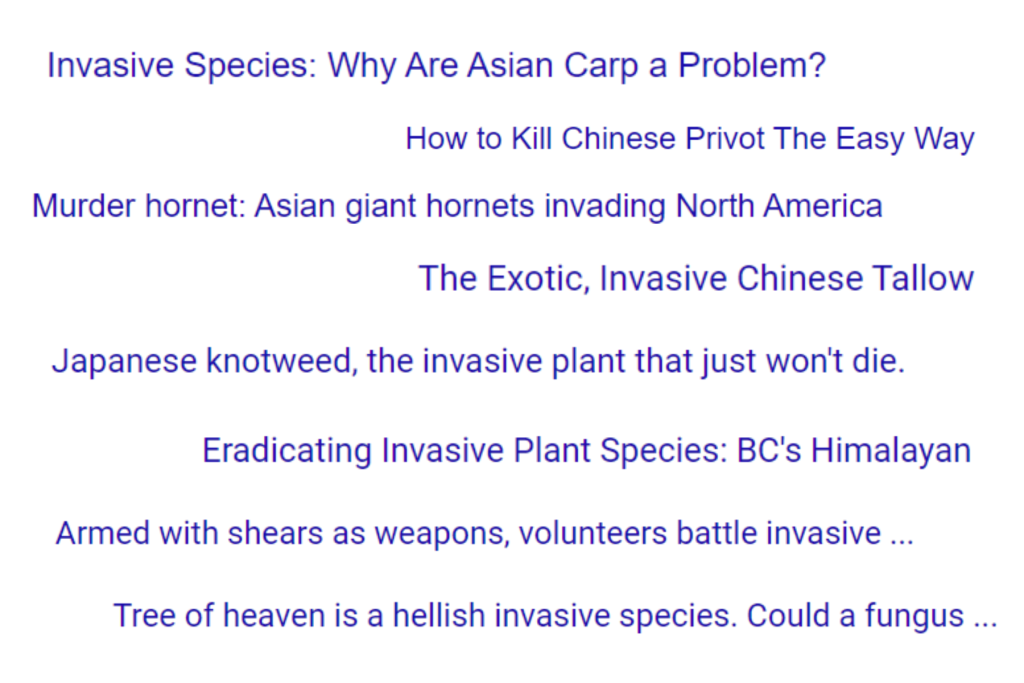

This same xenophobia is widespread in our stewardship work. Plant and animals are often named with the country or region from which they were taken: Japanese knotweed, Asian carp, Chinese elm. We label species as invasive, non-native, foreign, noxious, or alien or any number of disapproving characterizations. But why?

In 2020, Meera Iona Inglis’ published an article in the Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, titled Wildlife Ethics and Practice: Why We Need to Change the Way We Talk About ‘Invasive Species’, that described invasion biology as framed by Charles S. Elton’s in his 1958 The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants. He wrote:

“I have described some of the successful invaders establishing themselves in a new land or seas, as a war correspondent might write a series of dispatches recounting the quiet infiltration of commando forces, the surprise attacks, the successive waves…of attack and counter attack and the eventual expansion an occupation of territory.”

Othering and Aggressive Plant Descriptions

These plants did not displace themselves. Luther Burbank brought what he called Himalayan blackberry to the United States in 1885 because of its phenomenal ability to produce large berry harvests. Many ornamental plants, such as knotweed, butterfly bush and holly were brought to the United States because people liked how they looked. These plants were brought here for their positive qualities, and then when they fulfil their purpose in life, to grow, we begin to fear them. It’s only once a plant does what we don’t want it to that we label them noxious, invasive, a danger.

The names we give plants have significant meaning. For many of us immersed in the field of plants, for work or pleasure, we use these names daily. We associate emotions and feelings with them. When these plants are prescribed as native to the Pacific Northwest, we often give them names that describe how they look, or how they grow – trailing blackberry, red-huckleberry, and the ancestral language of the region, Lushootseed often does the same. When these plants are not indigenous to the Pacific Northwest, we often give them names that attempt to describe where they came from – Japanese knotweed, Himalayan blackberry. There are also cases where colonial settlers gave plants insensitive names such as Indian paintbrush and Indian plum. This reinforces our colonial mindset we have in the United States that white is the standard, and anything non-white is abnormal. Our plant names contribute to this standard.

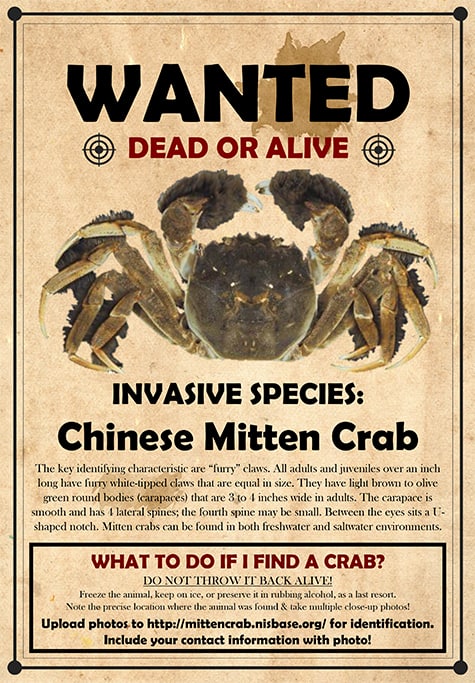

Then, on top of names that point to groups of people/parts of the world, we tend to anthropomorphize these plants. We give them human characteristics. “The Himalayan blackberry is invading our forest. We must kill and destroy all parts of the plant.” While we personify these plants, it makes it easier to forget that humans displaced that plant in the first place — that plant did not ask to be transported across the world out of the ecosystem in which it evolved.

Seattle Times published an article in February 2021 entitled Armed with shears as weapons, volunteers battle invasive plants in a King County park. This language, that is common-place in the environmental restoration field, prescribes militant action against these plants. It tells us we are at war against these plants that are not from here.

“Demonizing rhetoric portrayed unwelcome humans as foreign, alien, impure, invaders, and carriers of pestilence and disease. Such language justified atrocities to human life.”

– Celeste Mari Williams

The aggressive, othering language we use to describe plants can create an un-welcoming environment for people who identify as non-white. People who identify with the place names given to these “invader” plants can easily feel like this aggressive language is aimed at them in addition to the plants. We want our natural areas and forests to be places where everyone feels unequivocally welcome.

What Does This Mean for Our Restoration Work?

When we think of these plants as enemies, and use militaristic words to describe them, our response is limited to actions focused on destroying. We recommend eradicating invasive blackberry, by destroying their roots, and poisoning their leaves. We can recognize that plants like non-native blackberry wreak havoc on our ecosystems, and also recognize that aggressive language to describe these plants causes harm to our communities. Green Seattle Partnership is moving forward with actions to increase Just Language, including:

It Starts With Changing the Words We Use

- Remove location names: Call it blackberry rather than Himalayan blackberry (which is not even from the Himalayas, but was a name chosen by Luther Burbank when he brought it here). Don’t equate your dislike for the damage knotweed can cause in our PNW ecosystem to Japan or Japanese people. We recognize this requires a level of nuance. Should we remove locational names from predominantly white countries such as English Ivy and European Ash? (That’s a real question, we don’t know!) In addition, we can work to remove eponymous plant names (plants named after a particular person). Instead, we can name things after landscape or other natural features, like həʔapus Village Park & Shoreline Habitat.

- Remove aggressive language: Let’s call it what it is — we need to remove weeds. We don’t need to be at war with these plants. Consider how these words, paired with aggressive language can make people from those places feel. Also consider how using aggressive, war-like language to describe plants makes you feel in your relationship with them and our urban natural areas.

- Think about your relationship with these plants: Rather than thinking only about the negative parts, how can you recognize all the qualities of a particular plant in order to not develop a one-sided view of this fellow earth-dweller? Why was this plant brought here in the first place? Can you utilize this plant for food while removing it? How can we work with these plants; be in community with these plants?

- For the Green Seattle Partnership:

- Update to Crew Specifications – removes terms like “invasive” and “target weeds” as well as recent King County name changes for particular weed species.

- Using the First Lushootseed plant names – in our communications, plant lists and signage. Check out Lushootseed language resources: The Puyallup Tribal Language School, The Tulalip Tribal Language School, and Seattle University taqwšəblu Vi Hilbert Ethnobotanical Garden.

- Website and communication materials audit – in 2022 we plan to work through the GSP website and communication materials to remove mentions of aggressive invasive weeds such as the ‘Our History’ page seen below.

This is an ongoing conversation that we hope to continue with all of you. We all have the power to examine the words we use in order to ensure everyone feels welcome in our communities, parks, and forests.

Additional Resources:

- Just Language NW Website: http://justlanguage.org/invasive-species/

- Decentering 1788: Beyond Biotic Nativeness By Lesley M. Head

- Wildlife Ethics and Practice: Why We Need to Change the Way We Talk About ‘Invasive Species’ By Meera Iona Inglis

- Anishnaabe Aki: An Indigenous Perspective on the Global Threat of Invasive Species By Nicholas J. Reo & Laura A. Ogden

- Ecological Restoration, Cultural Preferences and the Negotiation of ‘Nativeness’ in Australia By David Trigger, Jane Mulcock, Andrea Gaynor, and Yann Toussaint

- Perspectives on the Alien ‘Versus Native’ Species Debate: a Critique of Concepts, Language and Practice By Charles Warren

- Unsettled Ecologies: Alienated Species, Indigenous Restoration, and U.S. Empire in a Time of Climate Chaos By Lisa Fink

- What’s in a Plant Name: Plant Common Names and the Stories They Tell By Rebecca Alexander

I’d respectfully suggest that if you really want people to use the Luhotseed names, you MUST provide a phonetic explanation of how to pronounce them in characters that can be read by a screen reader. It is expecting a lot of normally abled people that they learn a new set of characters, but perhaps it is reasonable… perhaps it’s a “big reach” that people should make on their way to redressing historical wrongs. But it is NOT reasonable to leave out differently-abled people on the way to that big reach.

I find this a fascinating and necessary discussion. I also agree with many of the conclusions. My question is, in a world where our remaining urban forest is sick, where trees are vital to mitigating climate change and more locally the urban heat island effect on the local waters, and developers are given a pass to take down all trees in lots they are developing, where does this leave us with respect to actions to protect these forests? I just finished reading Final Forest and one of the key points highlighted is that there is a human tendency to talk a lot, collect a lot of data, and agonize over the right thing to do in a way that allows the problem to get worse and more costly to fix. The Barred Owl, which is migrating naturally, might not have been such a threat to the Spotted Owl had action to protect old growth been taken sooner rather than later.

I did a quick read of this article; while I generally agree with the sentiment and the tone, I would like to offer 2 words of caution to those trying to move this issue in a progressive direction. I’m a long-time (since 1997) professional working in forestry and arboriculture with a Masters Degree; I’m now an urban forest manager. I suck at languages (well, my English is OK) and it’s been a struggle to incorporate Scientific names into my vocabulary for my professional career and I really can do so only when the term has been repeated to me A LOT. If the progressive direction of this issue is to rename plants and animals, especially using non-European based languages, it risks constructing a subtle (or not so subtle) barrier to the conversation which might be unintended. (Those who “name drop” scientific terms often seem oblivious that some people get lost when this happens; someone commenting on the beautiful foliage of the Acers deserves a “What?? speak normal!”)

The second challenge is to remove the stigma of those whose use old terms: will my age (55) protect me in a few years when I slip out “gypsy moth” or will my audience dismiss me as an old arrogant privileged person who has done nothing for the world (except maintain a 150,000 tree urban forest for 2 decades)? I recall the (unwarranted in my view) vilification a friend of my parents received from my friends for his use of the term “colored” in the early 1980s and it has never left me.

Those of us who have worked to remove non-native and aggressive species may legitimately regard this as a battle or war. Himalayan blackberry perhaps could be referred to by the botanic name instead, but it does need to be distinguished from native blackberry. The “Himalayan” species is extremely invasive and has completely taken over many acres of land where little else can grow. The same is true for Scotch broom and English ivy and Japanese knotweed. Maybe we could call the last one just ” knotweed.” I agree that language is important, but we do need to distinguish species, and most people do not use botanical or Latin names. I also agree that these plants did not willfully come here on their own, but many of these introduced species have become dominant and have a very negative impact on native species and habitat. If we value species diversity, native habitats, and endemic species, we must eradicate some introduced, invasive, and aggressive ones.