Seattle has 485 parks and natural areas. Ever wonder how they got there?

Each park has a unique story, a messy assemblage of history and ecology. Though this brief post cannot do justice to them all, it will tell a broad-stroke story of the park system.

Early Days

The Denny Party, credited as Seattle’s founders, landed at Alki Point in 1851. Here they found a dramatic landscape bounded by water and mountains and lush with old growth conifers. Within two years, these conifers fed Henry Yesler’s lumber mill across the harbor, where a village was starting to swell. In 1869, after several years of continued growth and Indian displacement, the village was officially incorporated as the City of Seattle.

Even Seattle’s early residents recognized the need for urban greenspace. So in 1884 David Denny donated five acres to the city to create its first public park. Others soon followed suit, creating Ravenna, Leschi, Madison, Woodland, and more. As the city’s tendrils of development continued to reach outward, pockets of green remained.

Calling the Professionals

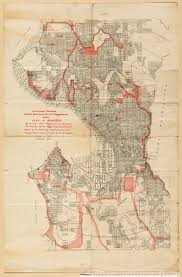

In 1902, the city decided to better coordinate its patchwork of parks. To do so, the City Council reached out to the era’s biggest name in landscape architecture, Frederick Law Olmsted, famous for his design of New York’s Central Park, Boston’s “emerald necklace,” and hundreds of other projects. Seattle was a bit late to the party: Frederick was well on the way to his 1903 death. The Olmsted firm lived on, however, and the council hired Frederick’s nephew and adopted son, John Charles Olmsted, to comprehensively plan Seattle’s park system.

The Plan

Rather ironically, Olmsted’s plan prominently featured a parkway – a scenic road running from Seward to Discovery parks. Along the way, it wound along the bluffs of Frink, down to the waterside at Madrona, over the ravines of Ravenna, and out to Greenlake. From there it cut through Woodland and eventually climbed back up to Discovery’s seaside cliffs. Spurs sent joyriders to Jefferson, Volunteer, Kinnear, and others.

The automotive optimism made sense at the time. What could be a more pleasant and efficient way to access so much greenery? But as the century progressed, the car dominance left a legacy of inequality and environmental degradation.

Roads aside, the parks were beautiful. Olmsted left some in their natural states, keeping for instance the towering Douglas-firs and dramatic ravines of Ravenna Park, while opting for manicured landscapes in others. Playgrounds were a novel concept at the time, but Olmsted embraced them, recommending playgrounds within half a mile of every house.

The city, acting on Olmsted’s plan, enacted large-scale landscape transformations as well, including draining Green Lake by seven feet to create an additional 100 acres of parkland. This came in a context of massive regrading projects, which sought to make development easier by simply flattening hills.

Post-Olmsted

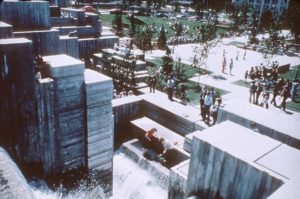

The history does not end with the city’s adoption of and expansion on Olmsted’s plan. Parks continued to emerge, thanks to a host of groups and individuals, as the city condensed into its current form. Some have been quite innovative in their reclamation of urban space, such as Freeway Park, which caps I-5 with a splash of greenery and Brutalist architecture. And dozens of projects are underway as I write, continuing to strengthen the city’s park system in the face of unprecedented population growth. Olmsted’s grand design, however, remains the foundation of Seattle’s open green space.

Want to be a part of the parks system’s living history? Come out to restoration events at some of the parks discussed in this blog post:

And find the full calendar of events here.

For more historical information, check out History Link and Seattle Municipal Archives.