Recently, I went to see a movie with my family during a sizzling summer afternoon. The irony isn’t lost on me that the sparsely treed streets outside most movie theaters are the hottest places in town. Meanwhile we sit in a comfortable air-conditioned environment to seek comfort from the heat.

Looking back almost a decade, the GSP blog has emphasized how climate disruption brings about vulnerability and negative impacts to our human communities and forest environment. And for good reason! In 2022 Seattle broke its historical record for most days 90-degree days in a year. Then, as early as mid-May of this year millions of people were placed under heat advisories as a heat wave brought extreme temperatures to parts of the Northwest. Summers of record-breaking heat reminds us that our neighborhoods are not getting any cooler. Sometimes, we can feel wedged between localized urban heat islands, prolonged droughts, smoke season, and heat events. While these changing conditions are already harming Seattle’s frontline communities and urban forest now, I would love to highlight our ability to adapt and care for each other in a warming world.

In Summer 2022, Seattle Parks and Recreation partnered with 12 other cities in a nationwide study led by New York City-based Natural Areas Conservancy. The study examined the cooling potential of forests and green spaces. In Seattle, we deployed six sets of temperature sensors citywide in parks as well as the immediate surrounding neighborhoods. The results were telling – July 31, 2022 was Seattle’s most scorching day last year where temperatures reached a maximum of 95o F. Though, you guessed it, the temperature under the tree canopy tended to be cooler. Read the full study results here.

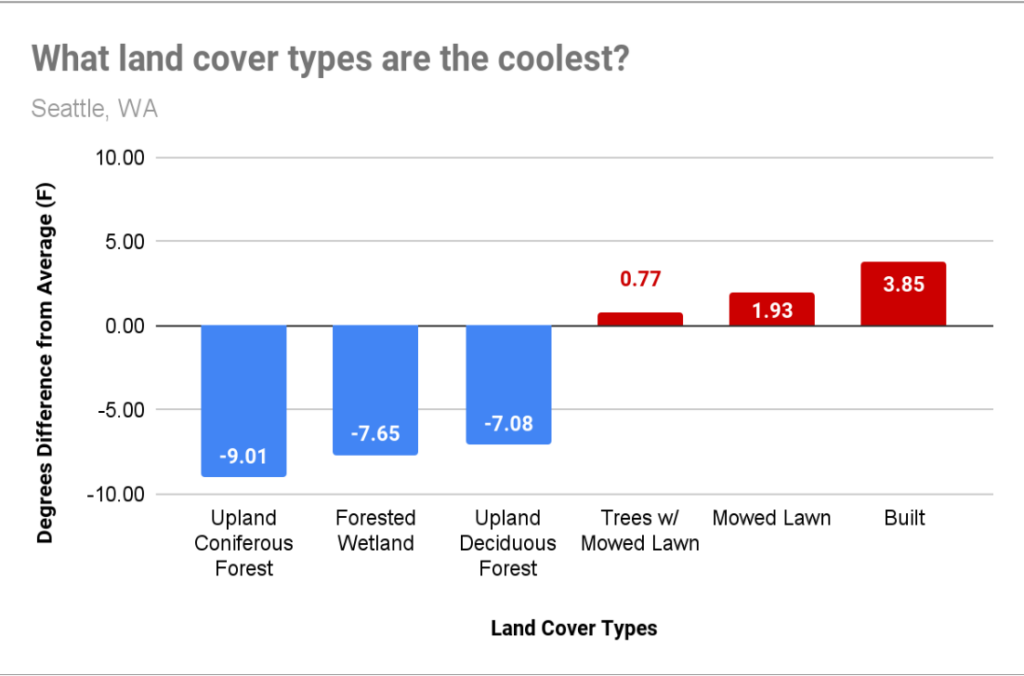

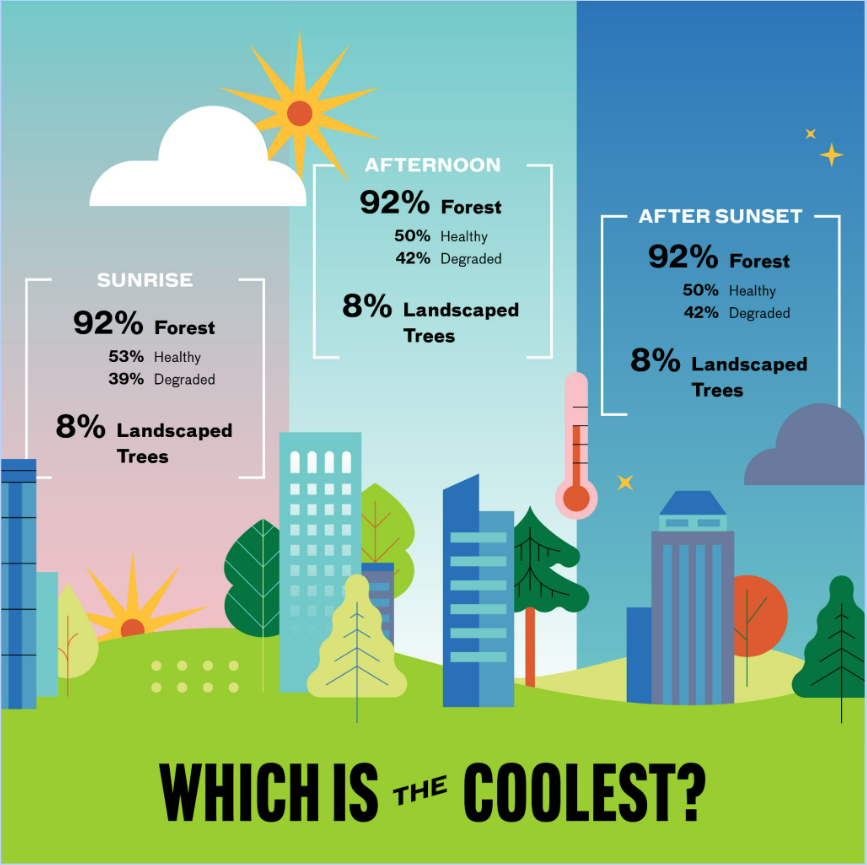

Top takeaways from the study were 1) natural areas land surfaces are the coolest – the maximum temperatures were lower across the board, sometimes by over 9o F; 2) natural area forests provide cooler air temp than isolated trees in the landscape; and 3) during the hottest time of day, more diverse forests were cooler than forests we wouldn’t characterize as healthy. We think the results underscore how caring for urban natural areas is a vital way to disrupt elevated urban heat.

Green and blue infrastructure provide essential community services. It’s important to note ALL trees and vegetation mitigate heat – deciduous, fruit tree, *invasive, “non-native”, conifer, tall and short. This occurs mostly through direct shading and evapotranspiration – the evaporation of water drawn from the soil to the leaves via transpiration. So, you have options when it gets hot outside. Specifically, the cooling study showed that forests with conifer trees had the coolest surface temps – so those may be the coolest places to rest, rejuvenate, and connect. I also want to put a plug in the longevity-boosting effects of wading (or jumping) into the cold nearby waters of Lake Washington, Puget Sound, or the closest spray park or wading pool. Want to learn to swim safely? Seattle Parks and Recreation’s pools are one of the best places to learn.

While I can temporarily retreat to a cool movie theater, none of us can permanently run away from heat-related stress in our daily spaces. In Seattle, heat tends to build up where the buildings and concrete are concentrated, far from heat mediating bodies of water, and where tree canopy is low. Heat continues to be one of the biggest killers of any hazard we encounter in urban areas. And heat-related impacts are exacerbated by the perpetuation of institutionalized racism, inequitable distribution of power, and lack of accountability.

Taking responsibility for tree equity and heat justice in natural area restoration and citywide tree plantings can partially address inequitable heat impacts to historically (and currently) marginalized neighborhoods such as formerly redlined areas in Seattle. It could actually save human lives.

In response to instability of climate and other overlapping crises we are facing, Green Seattle Partnership is dedicated to undoing racism and building racial equity, gender equity, and social justice into our sphere of forest-related programs and services. In 2021, GSP staff sought the advice and personal stories from park users and stakeholders as part of Seattle Parks’ 2022-2024 Action Plan. Results came back showing concerns and priorities for Seattle’s tree canopy in mitigating the impacts of climate change while also highlighting trail access and maintenance; pathways for job training, with a priority BIPOC communities; scaling urban canopy restoration across institutions & land ownership; more celebration and connecting environmental education!

Some very important and relevant data tells the story, and helps inform us about the barriers (and potential opportunities) to fulfilling the above-named actions. The King County street-level heat study of 2020 found that natural areas are some of the coolest places in the County, but also reveals that elevated heat follows injustice, asphalt and treeless neighborhoods.

When we take this further and mash up the street-level heat data + the City’s Racial and Social Equity Composite Index + the City’s most recent canopy cover change analysis, we begin to see where to prioritize investments to add/replace tree canopy and shade while also doubling down on establishment care, like providing adequate mulch and water.

With a community-centered framework, open data sources and sharing knowledge, we can also track the essentials that determine who has access to cooling, whether a neighborhood is surrounded by green space or asphalt, if a community has transit or walking access… just some factors that are crucial to whether community members can cope with and respond to climate disturbances.

Equipped with this knowledge, GSP will continue to revision and tighten our focus in a few areas including, but not limited to: restoration of climate refugia – areas with natural buffers to the warming temperatures – as sanctuary for sensitive tree species and protection for Seattle’s unique biodiversity, partnerships and programs that may better address Indigenous, gender, youth, and elder-specific needs, protection of shorelines and streams, and enhanced forest management in exposed hot sites that require creativity and grace.

Vital Signs for a Thriving Urban Forest and Vibrant Community There are a few “vital signs” that indicate a cool community and healthy urban forest.

- Rooted in discriminatory housing and zoning policies, formerly redlined neighborhoods generally tend to be warmer and less green than other neighborhoods within Seattle. These neighborhoods can be seen on the Mapping Inequality website.

- The difference in heat between communities can be visualized on maps from the Seattle & King County Heat Watch. The cooler areas (generally forest or water) show up as paler colors vs. vibrant colors for hotter areas.

- Per the Urban Forest Management Plan, the City of Seattle endeavors for 30% average canopy cover citywide though different land types have different goals to reach by the year 2037. For example, Park’s Natural Areas target is 80% canopy cover while the expectation for Multi-Family Residential is 20%. Canopy cover isn’t static and showing a slight decline between 2016-2021. Canopy change data from the last Tree Canopy Assessment will be available on the Seattle Open Data portal when it becomes available.

- The City’s Racial and Social Equity Composite Index is a composite of race, language spoken, ethnic origin, socioeconomic disadvantage, and health disadvantage by census tract. Similarly, an easy way to look at a combination of tree canopy cover, climate, demographic and socioeconomic data is to review your community’s Tree Equity Score.

Textbook ecosystem services like shade from trees are always emphasized as a natural climate solution. But there is no single universal remedy for cooling. Care for climate and community doesn’t always have to begin and end with the stereotypical tree planting. For instance, warming temperatures unsettle the conditions needed to grow local food like fruit trees and culturally significant plants. One may inadvertently harm family food security and compromise social justice if we stick to a shade-tree-for-all strategy in every neighborhood. Climate resilience may also look like tag-teaming projects with Seattle Parks and Recreation’s Trails Program to improve safety, access, and creating a welcoming environment within forested parks. It can also look like GSP-sponsored youth and skills-training programs focused on the multi-generational effort to steward climate-ready urban forests.

In June 2023, the UW Climate Impacts Group published In the hot seat: Saving lives from extreme heat in Washington state, which outlines specific, actionable guidance for short-term emergency response and long-term risk reduction. We have seen anchor institutions, such as Seattle Parks and Recreation, become de-facto or intentional resilience hubs that deliver essential services and mutual aid to our neighbors. In the last few years as we’ve lived through overlapping crises, we’ve also witnessed schools provide food to families. And we’ve watched libraries, pools, senior centers, community centers, and places of worship become cooling centers for clean-air relief during the season of wildfire smoke.

The absolute best cooling tactics are built on trust and require thoughtfulness and community leadership. Local residents are the authorities on where it’s hottest and which solutions make sense for their community. A climate of care is more than shade. It’s about seeding and embracing adaptation to change.

__

Please hydrate & check on your families and friends. Then remember, if we take care of the forest, it will take care of us by cooling the places we live, work and love. For your own climate and community care toolbox, below are some ways to engage:

- Learn more from the GSP network: Understanding Climate and Tree Canopy | Effect of Urban Heat Islands | Seward Park Audubon Center Wednesday, August 09, 2023 6:30pm – 8:00pm Seward Park Amphitheater 5900 Lake Washington Blvd, S, Seattle, 98118, WA

- Which public spaces could provide cool respite during a heat wave? Become familiar with the locations of forested parkland, shoreline street ends, beaches, and cooling centers

- Passion for Data? Follow links to track your neighborhood’s vital signs related to heat: tree equity score, Mapping Inequality of formerly redlined Seattle; King County street-level heat data, City’s Racial and Social Equity Composite Index, and the City’s canopy cover change analysis. Visit this slide deck for a descriptive summary of some high level results, and links to data from the Forest in Cities Cooling Campaign Media.

- Find a forest near you and help organize a GSP event: https://seattle.greencitypartnerships.org/event/map

- Plug into City of Seattle Safety Tips and Resources for Heat: https://www.seattle.gov/heat-safety

Postscript on tangential progress – Back in 2020, we published an early version of a Climate Change Vulnerability and Response in Seattle’s Urban Natural Areas foregrounding what we knew and efforts to date. In the early days of COVID pandemic, we convened the Forest Adaptation Network to share resources, discuss issues, and collaborate on forest adaptation projects regionwide. By January 2022, Seattle Parks released our Climate Resiliency Strategy. Urban natural areas were part of that action plan, but natural areas need to be funded, managed, protected, and maintained to contribute to climate mitigation. GSP is relatively privileged to be supported by Park District Cycle 2 – Restoring and Increasing Urban Canopy. Our approach to this work is grounded in the environmental justice principles outlined in the City of Seattle Equity & Environment Agenda and focuses land care on priority neighborhoods with BIPOC community collaboration and informed by race and social equity priorities, canopy change, and ground level heat mapping data. Meanwhile, the State of Washington launched the Washington Tree Equity Collaborative, aiming to expand canopy cover and promote healthier communities in urban areas where it is needed most. Without proper policies, funding and protection, the vast benefits of natural areas could diminish, leading to a hotter and less livable city.