Anyone who has worked with the Green Seattle Partnership knows that much of our work revolves around removing invasive plant species so that native plant and animal species can thrive. For much of the history of restoration our actions have been pretty clear cut: we remove invasives to protect natives. I’m going to discuss some reasons why we want to protect native species (hint: it’s not just because they are here), then I’m going to discuss reasons climate change might require us to rethink how we achieve these goals.

But first, some definitions

So we’re all on the same page I’m going to define some terms you may have heard before, and some you may not have.

Native species: a native species is one that either evolved in a region, or came there due to natural processes and successfully established a population. Animals that migrate, and plants that disperse their seeds by wind are examples of organisms who move to new areas via natural processes. Native species are often protected in managment plans.

Invasive species: these are organisms that came to new regions and established populations there due to human actions. These human caused introductions could be accidental or on purpose. Many aquatic invasive species have unknowingly been transported in the ballast water of ships. Many invasive plants were brought to new regions because people wanted to grow them in their gardens. Invasive species must also cause problems in their new region. English ivy is a great example of a plant that was brought to the US for use in gardens, escaped those gardens, and now threatens our forests by taking all available space. Managment action is often taken to persecute these species.

For a time, a species was either native or invasive. In this dichotomy native species are good, and invasive species are bad. We soon saw the need for a third category.

Non-native species: these species were moved to new regions through human activities, but do not cause problems in their new regions. A great example of non-native species are tomatoes, we brought them from South America to the rest of the world, but nowhere have tomatoes escaped their gardens and farms to take over the natural environment. Managers usually ignore these species.

These three categories of native, invasive, and non-native have been a part of our restoration and management framework for a long time. Lately though ecologists are recognizing a fourth category.

Native-Invader: this is one you may not have heard before. Native-invader refers to organisms whose ranges have expanded on their own, but who are still causing problems in new regions. You can read about some examples of native-invaders in the box above.

Why do we want to protect native species?

There are many reasons that ecologists, restorationists, and land stewards want to protect native species. Most of these reasons fit into one of three categories.

Protect Ecological processes

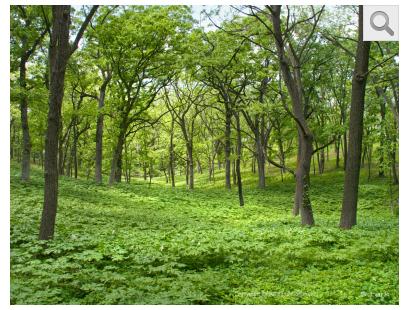

Our ecosystems are made up of interconnected food webs. Every member of the web plays a role in the habitat. If we start to lose different members of the ecoystem, effects cascade throughout the web. We go from a healthy, complex, functioning ecosystem to a non-functioning monoculture of just a few invasive species.

Protect Economic Value

Invasive pests and disease can decimate crops and forests and the costs of controlling an already established pest can be cost prohibitive. Preventing new invasions is often the best way to preserve the economic value of working forests, agricultural lands, and ecosystem services.

Protect Cultural Value

Many native species are significant because of their relationship to human culture. This might be an animal we grew up hunting with our families, or it might be a plant this is important to Indigenous peoples. This category can include organisms we would be sad to lose for no other reason than that we would miss them.

Managing Speices in a Changing Climate

One effect of climate change is continued warmth across the planet. All organisms have a temperature range they can live in. When their home region becomes consistently too hot organisms have three options: physically adapt to a warming environment, move somewhere cooler, or become locally extinct.

Physical adaptations take many generations, and many, many years to impact a population. At the rate our climate is changing many populations will not adapt in time to be saved. To avoid local – or global – extinction, populations are migrating their ranges pole-ward, or up in elevation, to escape warming temperatures and find a cooler habitat.

Researchers at the University of Washington created this map to visualize the projected migrations of mammals (pink), birds (blue), and amphibians (yellow) in changing climate conditions. You can read more about their research and see the full map here.

So in our existing framework we’ve considered native, invasive, non-native, and native-invading species. But where do these migrating populations fit in? Migrations and range shifts are a natural process, and many of these organisms are doing all they can to survive in a shifting climate. Some may cause problems in their new ranges, some may not. Some may fill a niche that another migrating population left vacant.

This brings us to yet another category of organisms – a category that is currently creating questions for land managers, researchers, and policy makers: Climate-driven invaders. These organisms are ones whose ranges are shifting with the climate. Of course range shifts are normal. But what we are seeing now is about half of all species shifting their ranges between an average of 10 and 40 miles per decade. This means that we will continue to see new species in our environments that do not fit into the native/invasive framework we have based management decisions on for so long. It means we have to start asking ourselves some tough questions.

What are We Trying to Protect?

Climate-driven invaders force us to define what we are trying to protect or maintain in our restoration and stewardship activities. Only then can we choose the right actions. They also require that we think across geopolitical boundaries, and in larger timeframes than we are used to. It is time to get very specific about our restoration goals!

Ecological Processes

If our main goal is maintaining functioning ecosystems we may be less concerned with the individual species that make up the ecosystem. In this example we may be more likely to accept the presence of a climate-driven invader if it replaces another species that is no longer present. This is why some land managers accept the presence of invasive barred owls, and do not think we should try to remove them from the west (see Native-Invader box above).

The question we need to ask ourselves in this scenario is: Does the climate-driven invader fill a productive role in it’s new ecosystem?

Climate projections in New England show that oak-hickory forest will likely replace maples. The US Forest Service is examining the effects of this shift on the forest ecosystem. Importantly, they are also analyzing parts of Canada as the ecosystem crosses political boundaries.

Economic Value

Sometimes the economic value of a species is the top priority. Economic value may need to be protected by removing invasive species, or protecting natives. There are many cases where economic value trumps ecological processes, especially when it comes to food production.

When thinking about economic value we must ask how will our economies need to shift with the climate? How will we work across borders to support ecological and human communities that are affected?

Johnson Grass Threatens Crops

Fisheries Shifting Northward

Fish in European waters are on the move. Capelin have left Iceland for cooler waters, while mackerel have moved from Britain to Iceland. While Iceland increased limits on mackerel as they increased in abundance, the EU was simultaneously trying to lower limits to protect their own dwindiling stocks.

Cultural Value

I’m sure you can think of a species that feels culturally important to you. Personally, I love hiking in the shadows of Douglas fir, they make me feel like I am home. If our PNW Douglas firs start to shift their range I will be sad. But remember, range shift are a natural phenomenon. They are one way species show their resilience in a changing world. As stewards and restorationists they remind us that we must be resilient and adapt as well.

We can ask ourselves: how can we best support species resilience? Where can we best direct our limited resources in a changing environment?

Is it advocating for increased monitoring and science based policy? Creating more wildlife corridoors? Sourcing your seeds from farther south or even planting a non-native plant that might succeed farther north?

Considering Assisted Migration

Coastal redwoods and giant sequoias – the tallest and widest trees respectively – carry meaning for many people. Restricted to California, their ranges are currently shrinking. And because they live thousands of years and reproduce very slowly they are unlikely to shift their ranges at the speed of climate change. This has led to “assisted migrations” where redwoods and sequoias are planted north of their current range in an attempt to help the trees migrate.

Quiver Tree Management Across Borders

Quiver trees are only found in Namibia and South Africa and are currently threatened by a changing climate. Management is complicated by the fact that populations are decreasing in Namibia, but may be increasing in South Africa. This is a great example of the need for cross border management that considers the population as a whole. How can conservation efforts be coordinated for cross border protection?

What Now?

Many of the questions I ask here do not yet have clear answers. And unfortunately, with the rate that our climate is changing we may not know the impacts range shifts will have until after they have happened. One way we can be prepared for these changes is by paying attention to different ecosystems, restoration programs, policies, and research studies. The more examples we see of adaptive management the better equipped we will be to make flexible, informed decisions about our own stewardship decisions. We know that changes are coming, so let’s start a conversation now about what our goals are and how to achieve them.

If invasive species are not trespassing the niche boundaries of native ones ,then they need not to be thought as culprits.