Photo by Todd Parker

Planting for the Future

Here at the Green Seattle Partnership, we’re very excited about ecological restoration! We’re grateful to have done critical work with volunteers to reclaim and restore urban forests by removing aggressive weeds and planting native plants in parks all across Seattle.

While weed removal and maintenance is an important part of that work, we’ve been in the midst of planting season and have planting on the brain. During our events, many of our volunteers like to know what we are planting, and why we chose those plants. That question is big, and the answer could probably span several blog posts (or an introductory course in ecological restoration). Instead of getting into all the nitty-gritty details, we’ll tackle one aspect of it: structural diversity.

What is Structural Diversity?

We often hear about biodiversity, which typically refers to having a variety of species in the same habitat. In a nutshell, having a diverse group of plants makes for a more resilient forest, with a greater range of resources for wildlife. Structural diversity on the other hand is related, but different. Different plant species grow to different heights, and the variety of these heights is a major component of structural diversity. A healthy urban forest should have several vertical layers, ranging from mature trees all the way down to wildflowers.

Why is this important?

There are lots of reasons forest structure is important, but we’ll highlight a few of the most important ones:

I. Long-term outlook

A forest with lots of tall trees but no young trees or plants on the forest floor is unlikely to be healthy for the long stretch. People often say that children are the future; well, saplings are the future too!

One of the major challenges facing Seattle’s forests is the lack of young conifers. While our native deciduous trees (like bigleaf maple and red alder) are great, they live much shorter lives than our conifers. Healthy western redcedars are known to live in the ballpark of 1,000 years!

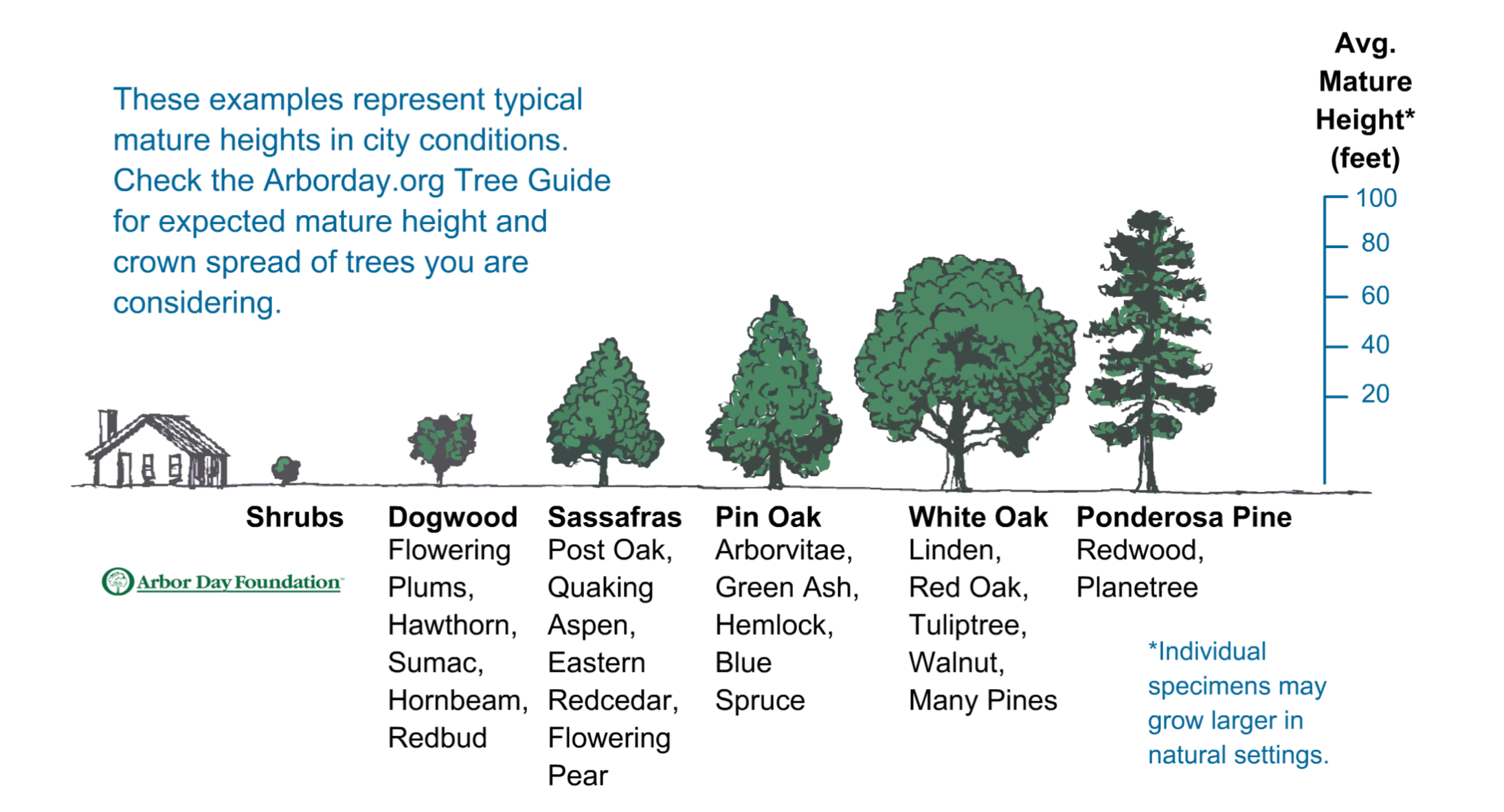

This is why it’s important to not only have mature trees, but mid-story trees, and young trees. As shown in the figure from the Arbor Day Foundation below, trees come in many different sizes, and thus there are many different tree layers. In the PNW, we’re looking at mature conifers such as Western redcedar, Western hemlock, and Douglas-fir to make up the tallest tree layer. On the other hand, trees like Pacific dogwood will grow to a mid-story level at the highest. These different trees occupying different layers of the forest creates structural diversity!

II. Staying competitive

Aggressive weeds such as English ivy and Himalayan blackberry thrive first in open, disturbed areas. Then, they’re able to migrate from forest clearings or edges into intact, mature forests. In general, aggressive weeds thrive in high light areas, which typically are areas lacking in structural diversity. Mature trees provide a good deal of shade, but mid-story trees and tall shrubs are also important for casting shade and blocking out weeds.

III. Wildlife

Structural diversity plays a key role in wildlife diversity. Species ranging from pileated woodpeckers to garter snakes have very different life strategies for finding food and shelter. Having a variety of plants creates the structures that different animals require.

Studies have shown that plant species diversity is not nearly as important as plant structural diversity in determining wildlife diversity. There are a few components of forest structure that are particularly important for wildlife, including 1) large live trees; 2) large dead trees; 3) coarse woody debris; and 4) height diversity. In essence, having a mixture of these elements creates micro-habitats within the forest, and allows for many different types of wildlife to co-exist. As an example, pileated woodpeckers require large, standing dead trees and downed wood to establish themselves. On the other hand, studies have shown that small mammal communities are strongly impacted by the shrub and herb layers, which they use for foraging and shelter. Restoring urban forests to attract wildlife will require attention to forest structure, and planting plants accordingly.

a look into the layers

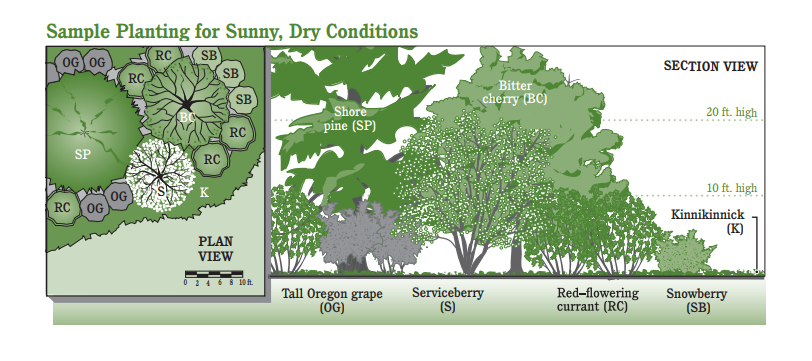

So what would a complex forest structure actually like? Below is a diagram from King County’s Department of Natural Resources and Parks, which shows a planting plan with a diversity of heights. You can see how taller trees form the canopy, while shorter trees and shrubs make up multiple mid-story levels, and kinnikinnick is the dominant ground cover. While this is taken from a native plant landscaping guide, the principles can be applied to restoration work.

Further below you’ll find a series of image galleries that will show you some of the plants species that occupy the canopy, mid-story, and ground cover layers. Feel free to peruse at your leisure, and think about your next restoration project!

Planting with a plan

When we’re choosing plants for our restoration sites, there are a lot of things to keep track of! Site characteristics such as moisture, sunlight, site history, and many more can impact what plants will thrive or struggle at the site. However, we do know that all urban forests benefit from structural diversity! When we choose plants for restoration site, we try to make sure that site gets a good mixture of canopy trees, mid-story trees, shrubs, and ground covers. This diversity will ensure that our future forests remain healthy for generations, with plenty of opportunity for an abundance of wildlife to live and thrive in our communities. So the next time you’re out in your local urban forest, take a look! See if there are healthy plants in every layer of the forest. If there isn’t, get involved with us at one of our volunteer events, and enjoy some planting!