Climate Ready Urban Forests

Constant natural environmental change from wind, droughts, and floods have helped build Seattle’s forested areas into the warehouse of biodiversity that we know today. In many ways they are not fragile, but on the other hand, the colonization and development of the land that built our communities has drastically compromised the capacity of the land to support forests. On top of this compromised capacity, climate change looms large as a global scale phenomenon that threatens to drastically alter forests , in ways both predictable and unpredictable.

From the plants’ perspectives, changing climate isn’t exactly a new phenomenon; climate has always sent signals to plant populations to respond by adapting in place or moving. However, the current pace of human development and emissions is pushing the rate of climate change faster and faster. Now more than ever, the effects of climate change are becoming more apparent. We love the 2700+ acres of forested natural areas out there, but they are increasingly vulnerable as the affects of climate change intensify.

More than just climate change

While climate change gets all the buzz, humans impact ecosystems in a number of other ways as well. Many of the human impacts on ecosystems also reduce the capacity of ecosystems to fight climate change as well. These other impacts include:

– Movement of soils

– Removal of woody debris and animal species

– Introduction of non-native species

– Fragmentation/isolation of forested patches.

Assisting Forests’ transitions to climate change

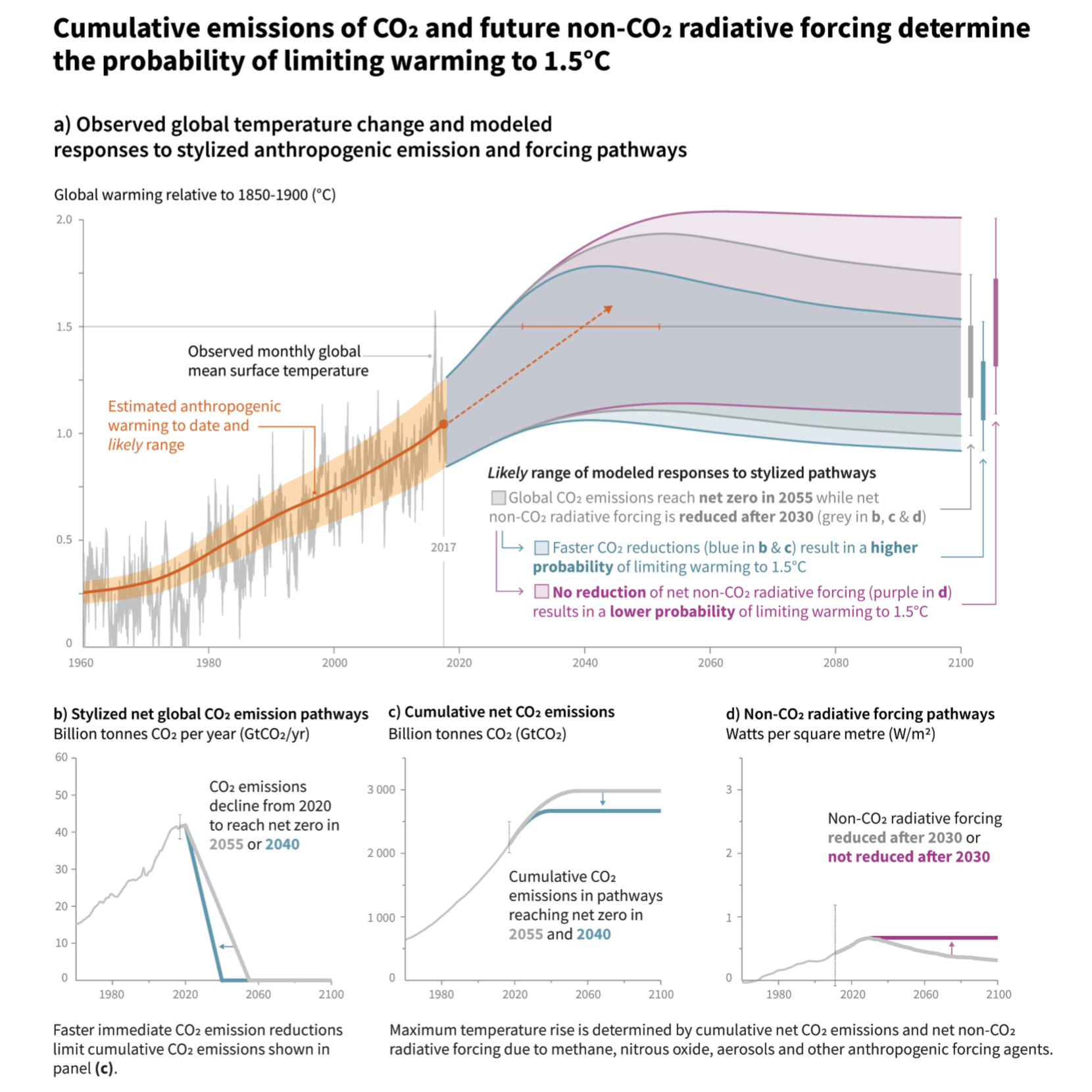

While there are international efforts to limit global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, We are currently trending towards 2 to 4 degrees of warming. Some research suggests Seattle’s late 21st century climate analog may lie close to Portland, OR – more than 150 miles away in our adjacent ecoregion to the south. With this information, GSP is developing a variety of strategies to resist, enhance resilience, and respond to climate change. Working on our climate readiness, one of our main tasks is to find ways to identify appropriate species for temperature increases, rainfall variability and associated climate impacts. This work helps build our long-range perspective while offering immediate actions in our pursuit of the highest level of ecosystem recovery attainable in our city.

Graph provided by the IPCC

A recent vulnerability analysis of Seattle’s forested parkland indicates almost half of natural area parks have risk factors that impact long-term forest health and resilience to bounce back from environmental change. Factors involved in climate change vulnerability include: proximity to urban heat islands, timing and intensity of rainfall, and lack of species diversity. Vulnerable habitats will be susceptible to drought, insect and disease mortality.

More broadly, this means the climate niche that local plant populations live within can uncouple from where they are currently located. Plant populations may become “maladapted” or less adapted to Seattle’s environment as the climate changes.

While there are risks to characteristic Northwest species such as bigleaf maple, western redcedar and western hemlock, there are also may be opportunities to honor and expand unique forest types that include Garry oak and Pacific madrone. While some local tree populations will endure future climate transitions unscathed, our strategy and action is to plant a more diverse mix of species to help mitigate the impacts of climate change in the city. We shouldn’t give up on our local trees, but we also think we should gradually shift what we are planting – at least to keep up with warming that has occurred already in our cities.

Expanding seed provenancing

This is where assisted gene flow or expanded seed provenancing comes into play. The adjacent tabs provide definitions to key concepts in climate transitions.

As of now, we at the GSP have yet to sink our teeth into the practice of introducing species outside of their native range. That’s because we still have genetic options available to us informed by our native reference ecosystems while still considering environmental change. In other words, we still have local species that can handle future climates, and we can continue to plant and support those species.

While “local is best” has been the de facto strategy in sourcing native plants, today we think we know local adaptation varies by species, population, and habitat regardless of geographic distance. Since the inception of GSP, we have intentionally or unintentionally acquired plants from a wide range of nurseries in the Puget Trough. Sometimes, seed and plants have come from as far away as Idaho and Oregon if project managers don’t specify the “provenance” of the material. Outplanted into a restoration site, those foreign plants flower and seed and are mixing genetically with our local plant populations. This can be a good thing as natural selection may lead to certain adapted traits and genetic variability. With some hope, I am optimistic that this hodgepodge of multiple seed sources—which has increased biodiversity— will help buffer our forests against the uncertain climate transitions we are yet to face.

Provenance

The ultimate natural origin of an individual plant or population, which could broadly mean geographic origin, nursery/seed house of origin, and method of propagation.

Assisted Gene Flow

Assisted migration

The “intentional translocation or movement of species outside of their historic ranges in order to mitigate actual or anticipated biodiversity losses caused by anthropogenic climate change.”

There some good candidates for assisted migration living among us, like coast redwood, giant sequoia, and incense cedar

Puget Trough

What is the Puget Trough anyway? It’s just a fancy way of describing the eco-region that we live in. It runs the length of Washington State (north-south) between the Olympic and Cascade mountain ranges.

GSP is going further

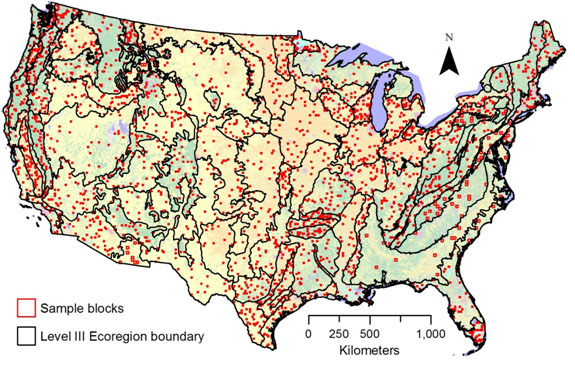

Given the context of what I explained above, Green Seattle Partnership is going further (literally) to source keystone evergreen trees from more distant seed provenances in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Our focus right now is on the longer-lived trees, and we don’t expect to do the same for the shorter-lived plants. The Puget Sound and Willamette Valley Level III Ecoregions are adjacent to each other, connected at an extremely constricted near-sea level point along the Lower Columbia River near Longview and extending south just past Eugene.

Working with professional contract crews during this 2019/20 season, we planted Douglas fir, Western redcedar, Western hemlock and other evergreens sourced from Oregon nurseries. In the case of Pacific madrone, we were able to acquire a small quantity of plants from even farther afield with more exact data about the origin of the seed. These trees look almost exactly like our local trees, and we are now taking extra effort to tag and track the importation of plants into our restoration zones around the city.

Bringing southern seed sources north to Seattle may augment diversity of tree populations over time as we encourage recovery though natural ecosystem processes. This more defined climate-adjusted provenancing strategy means seed sourcing “toward the direction of predicted change.” This includes local ecotypes and over time will gradually incorporate more distant genotypes as one combines material from more arid sites. For example, the typical winter in Milwaukie, Oregon is 1.3°F (0.7°C) warmer and 0.5% wetter than winter in Seattle. We are going to be looking for winning traits, such as the (idealistic) adaptive capacity to hang tough with fluctuating soil, or the more extreme hot and cold temperatures that are expected with climate change. These winning traits will allow us to restore towards climate ready urban forests.

This seems like a safe jump to make while we explore our options, “dial in” our seed source selection, make inquiries with experts in the field, and vet the idea with our stakeholders and partners. However, some modelling we have carried out using the Seedlot Selection Tool suggests that we could pull seed sources as far away as the foothills of the Siskiyous and Klamath mountains and down into California.

Concluding Thoughts

What is fascinating to me is what role hope and doubt plays in our outlook on future climate uncertainty and our decisions about sourcing plants. One may be hopeful about the ability of Western scientific studies to provide us with data and information about genetic options.

Conversely, we may also be extremely doubtful about international efforts to limit global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels. We are trending towards 2, 3 or 4 degrees of warming with past and present greenhouse gas emission trajectories. How will our future forests respond to that intense climate signal?

This will be an interesting time to monitor climate transitions, with a lot of things to keep an eye on! We will need to be diligent about keeping up with the latest findings and recommendations from Western science. At the same, we’ll need to take into consideration local observations, expertise and traditional wisdom. We’ll have to watch and see how these new trees “perform,” and become part of our changing landscape.

Of course, this isn’t going to happen overnight! It can take ten to thirty years in some cases for these trees to reach sexual maturity and start mixing genetically with our local tree populations. But it’s important to remember that like all our work we do to restore and manage the forest, this is a long-term investment into the stewardship of our environment. Staying informed about climate transitions and acting accordingly will help to ensure that our families and neighbors actually have future forests to enjoy.

How confident are you that public policy will accommodate these recommendations?

These are adaptation “actions” already broadly built from a policy foundation in City climate plan (2013), climate preparedness strategy (2017) and more specifically espoused in the last urban forest stewardship plan. The urban forest stewardship plan is currently being revised and a draft plan will be available for public comment some time soon http://www.seattle.gov/trees/management. That may be a good time to chime in if one is interested in engaging with public policy on this issue.